We sometimes hear stories of a school student who feels out-of-place, misunderstood or confused, until a teacher recognizes something unique about that young person. Then, through extra one-on-one attention, a special study project, or just consistent kindly encouragement, the teacher works some magic, applies some humanity, which suddenly opens up the world for that student—and they blossom.

Browsing through records in the Wilson Archives proves that University School, St. Michael’s, and SMUS have had teachers who sparked many student “ignitions” over the years.

I had a few excellent teachers and professors from K – BSc but none had any life-changing effect on me. Then recently, during my volunteer hours at the archives, I realized I had had such an ignition due to a teacher.

Mr. Caleb's Summer Tours

The experience occurred in the first hour of landing in England on the 1967 summer tour of Europe led by Peter Caleb. While our tour bus from Gatwick Airport to the hotel in central London was idling at a traffic light, I watched three local Council workers repairing the sidewalk. I had witnessed the same work in Victoria many times. But here, everything seemed different: the bib overalls instead of blue jeans; the unusual design of the wheelbarrow; the use of paving stones instead of poured concrete slabs; the ochre colour of the soil. And we were driving on the other side of the road! I was exhilarated.

By the time the bus began to move again the desire to travel was born in me and, starting after high school three years later, I began to fulfill it. The impulse was so strong that I must have had the seed of it somewhere in my soul already, but on June 29, 1967 Peter Caleb’s tour midwifed its birth—a red light turned green.

Peter’s name is well known at SMUS. He was one of a group of young masters from Britain who enriched the school with their arrival on staff in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Peter started to teach at University School in 1960, transferred to St. Michael’s in September 1964, became only the third headmaster there in 1969, and then the first headmaster of the amalgamated St. Michaels University School in 1971.

At the end of his first year teaching in Canada, as a young, cash-strapped school master Peter had no funds with which to travel back to Britain to visit his parents. But he and Nick Prowse, another young master at University School in the same boat, came up with the idea of leading a few students on a tour of Europe as a way of subsidizing their family visits back home. Et voilà!, the summer tours were born.

To quote one tour prospectus: “Travel is possibly the finest way of learning. The classrooms are the countries which are visited and the experiences gained are never to be forgotten.”

The first tours led by Peter and Nick, though small—six to eight boys—were still a “grand tour” of western Europe, with Peter driving a small van, luggage on top. In 1963 Ian Mugridge replaced Nick Prowse and there were 19 boys, including several from Shawnigan Lake School.

Peter was an excellent organizer. He began to make reservations, by letter post, in September for the next summer. He gave slide shows during the school year to attract “customers.”

In the summer of 1964 there were nine boys, all from grades 11 and 12 at University School. That year the tour had a couple of unusual features. Peter drove the Grade 11s across Canada and down to New York in his AMC Rambler American, where they left it and took a ship to Southampton. (The Grade 12s flew over a few days later after writing their provincial exams.) And when crossing from England to Belgium, Peter drove the rented 10-seater Thames van onto a front-loading airplane, which flew them to Belgium.

The next year the group included eight boys, seven from St. Michael’s and one from University School. Peter had married Diana Nelson in the spring of 1965 and the couple adapted the tour as their honeymoon. They rented a 12-seater Bedford mini-van. The six-week itinerary encompassed England, Wales, France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Italy (audience with the Pope), Alassio (on the Italian Riviera) for five days, southern France, Paris, Ypres (again), London.

Prior to 1965 the tours had not included Germany. Peter had a bias against that country at first because, when he was a schoolboy during World War 2, during an air raid he was hit in the leg by some shrapnel. The “angry” looking scar was visible even in his later life.

By 1967 the number of tourists had increased to nearly 50, accompanied by four or five chaperones. About half the students were girls, the ages ranged from 12 to 20, and they were drawn from a number of public and private schools in Victoria, Vancouver and perhaps Seattle, with two from university.

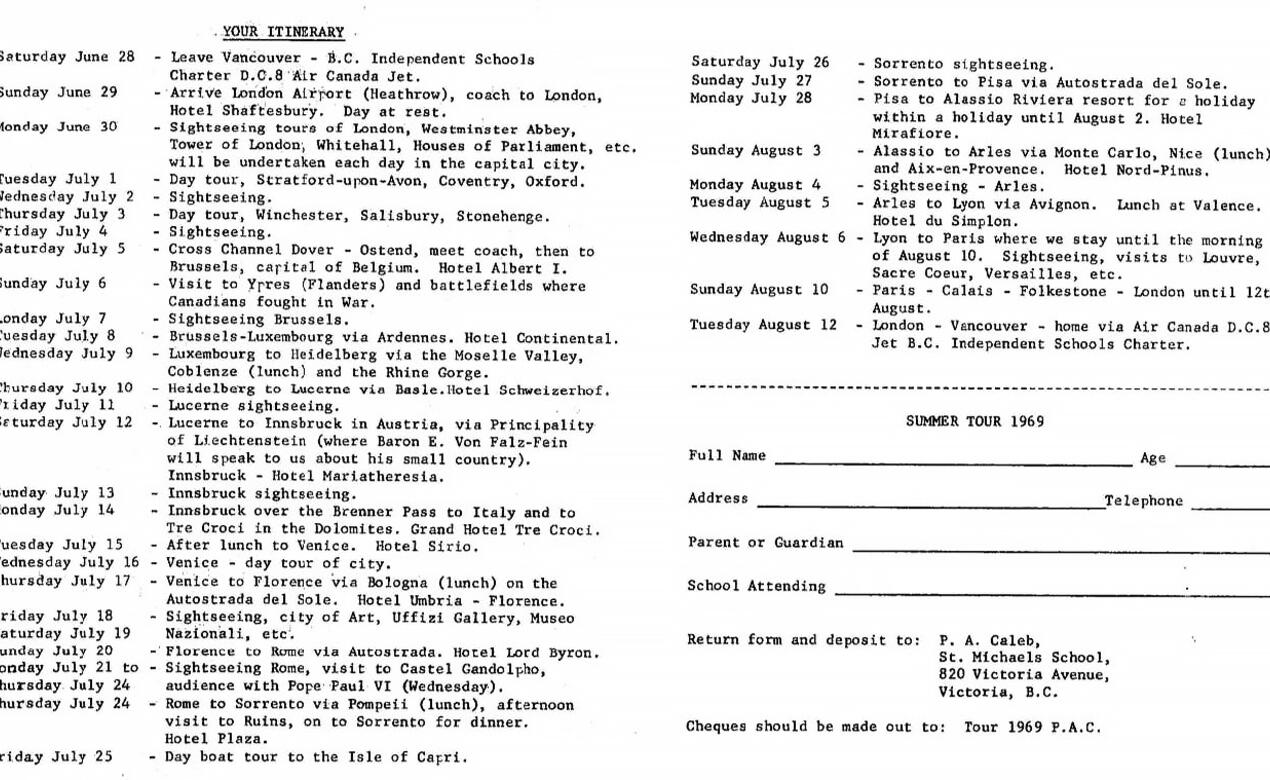

The 1967, ’68 and ’69 tours were probably the largest, and 1967’s was the longest, with an extra few days added at the end of the tour in mid-August for a Montreal stop-over to visit the World’s Fair, Expo ’67. Otherwise, those three years were nearly identical. A prospectus for 1969 has surfaced, with the full itinerary.

For each of those years, the cost was the same: $1,250 US, which included the flights, the big tour buses in England and on the Continent, accommodation in comfortable hotels, all meals, and entry to the “principal museums, art galleries and palaces visited.”

Which year the tours ended is not clear, sources differ, but 1973 may have been the last one because Peter’s responsibilities at the amalgamated school had expanded dramatically and his summers would have been filled with more work.

Highlights

I suppose that, for most of the young people, their summer tour with Mr. Caleb was just another holiday, albeit a pretty glamorous one. But because of the length of the trips, and by living in such proximity to the other members of the group, students had a chance to make friends with someone new to them. For “unisex” private school boys, it was also a chance to meet representatives of the other half of the world’s population.

Mr. Caleb certainly treated the young people in his charge as adults, at least more as adults than had been the norm while actually in school. We were allowed to attend a few night clubs, and the Folies Bergère or the Lido in Paris (in truth, only PG-13 ratings). On occasion we were allowed to drink a glass of wine—as European children did. One tour ‘alumnus’ went two years in a row. The year of his second visit, on arriving in London Mr. Caleb informed the first-timers that they were not to stray far from the hotel—unless they were with this alum, in which case they could go anywhere they wanted. It made that 13-year-old boy accept the mantle of leadership. And in being treated as adults, most of the students behaved that way.

More than a few “fell in love” with one of the countries they visited. Italy was mentioned in this way more than any other. For all of us it was an opportunity to see with our own eyes places, buildings or art works we had long heard of: Stonehenge, Stratford-on-Avon, Pompei, the Eiffel Tower, another tower in Pisa, the Coliseum in Rome, the Mona Lisa, and Michelangelo’s David.

Sometimes the favourite experience was of a city, like Paris. One boy who went on two different tours quite a few years apart thought Peter was very generous. In Paris he dined the tourists at Maxim’s, the world-famous restaurant.

Lowlights

Thinking back on those days, I marvel that Peter Caleb so easily accepted the responsibility of leading up to 50 adolescents across Europe for several weeks. There were other chaperones, including women for the girls. Nevertheless, he had the full weight on his shoulders.

Over a dozen or more tours, and inevitably with young people, there were some crises. A few of the difficulties were major ones. On what may have been the last tour, 1973, the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and European currencies had fallen so much by mid-summer that Mr. Caleb had to contact the parents in Canada to request their decision on (a) sending more money or (b) shortening the trip. The tour was cut by a couple of weeks.

In Rome one year it was discovered that, after a morning visit to the Colosseum, one of the students had not gotten back on the bus and it left without him. He walked into the hotel that evening after wandering around the city for many hours—completely lost, and with no memory of the name of his hotel or its address. A ‘buddy’ system was instituted so that it could never happen again, but the strain on Peter that day (potential telegram to parents: “I regret to inform you that I have lost your child”) must have been enormous.

On one tour—while on the continent—the bus driver and a couple of the students were standing in front of their hotel when it was struck by lightning, which ran down through the building, and into the bus. The driver was knocked through the front doors of the hotel and landed at the foot of the reception desk; he was shocked but otherwise alright.

Most of the problems were much less critical but still had to be solved: passports were left on buses; kids became sick or suffered minor injuries; roommates didn’t get along, and had to be switched; jokesters evolved into troublemakers; inappropriate purchases were returned with both the vendor and the purchaser feeling Mr. Caleb’s wrath.

Lasting effects

Educators have long recognized the value of out-of-school experiences for broadening and deepening the formation of young human beings. SMUS has a long history in this regard, and the practice continues with the Experiential Program, career and life education, outdoor ed, and more recent European tours.

My generation of students owes their parents a great deal for paying for us to go on Mr. Caleb’s tours. Though they were all conducted in the pre-oil embargo era (when transportation costs were much lower than they are now) the cost was not cheap.

But the greatest appreciation is due to Peter Caleb who understood what an extraordinary educational experience his trips could be for a young person: “…the experiences gained are never to be forgotten.” It is a failure on my part that I never sought out Mr. Caleb to tell him how that tour literally launched me into the rest of my life. This story is one way of expressing my thanks to him.

Since Mr. Caleb’s summer tour, Michael Nation (SMS 1970) has worked in a wool factory in Auckland, mined potash in Saskatchewan, seen the sun at midnight from Nordkapp, ridden a camel through Kordofan, walked to Lake Turkana, sailed across the Red Sea, provided primary health care to refugees in The Sudan, managed a feeding program in southern Malawi, taught logistics in Zaïre, played cricket in Yorkshire and lived in Cairo. If any other school alumni would like to share their story of how a University School, St. Michael’s or SMUS teacher helped them “blossom,” please contact Michael through [email protected].