Sitting down to write an article in honour of Asian Heritage Month can, at first, feel a bit daunting. Where to start? There are just so many cultures, traditions and histories to explore, commemorate and celebrate…

Unquestionably, the more that I learn about Canada’s past, the more I realize just how profoundly our local community, our wider province, and indeed our entire country has been shaped by centuries of interaction with Asia.

Think about it: the first Europeans to set foot in the Americas in the 1490s did so in search of a new route to the fabled riches of Asia. And when Captain Cook’s expedition returned in 1778 from its initial encounters with the Indigenous Nuu-chah-nulth peoples of Vancouver Island’s west coast, it was the astounding profits that the crew gained from trading sea otter furs in Chinese ports that kicked off the colonial scramble for what would become British Columbia…

Jump ahead a century, and you would find 17,000 labourers from southern China braving harsh terrain and unsafe working conditions to complete the most challenging sections of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) -- the most ambitious of nation-building projects, without which Canada might never have stretched “from sea to sea”.

Fast forward another few years and you would witness the first immigrants from Japan and South Asia beginning to make their mark, overcoming hostile immigration policies and widespread prejudice to build a better life for themselves, and enrich our local communities in the process.

And that’s before we even consider the last one hundred and twenty years!

Clearly, we, as Canadians, have a rich tapestry of Asian heritage to celebrate. But this year is particularly significant for our vibrant local Chinese Canadian community. This year, they celebrate four significant historical milestones — milestones that we should all commemorate with them.

After all, in our current context, we tend to make a big deal about hundred-year anniversaries, and with good reason: centennials offer us the chance to reflect back on the important past events that have shaped our present. And they often remind us just how far we have come.

That’s definitely true of the 2022-23 school year.

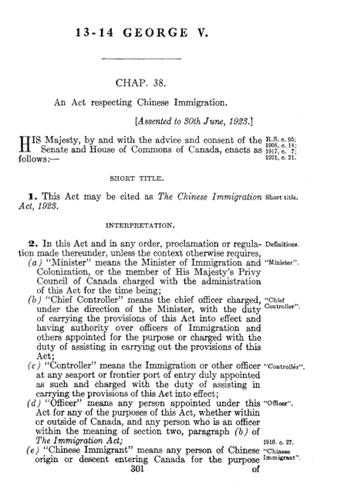

For one thing, it was a hundred years ago, in 1923, that the Canadian government enacted the “Chinese Immigration Act”, a law more appropriately known as the “Chinese Exclusion Act”. Under intense public pressure, particularly from British Columbia’s provincial politicians, the Federal government agreed to replace the so-called “Head Tax”, a series of progressively more severe immigration restrictions that were introduced beginning in 1885.

The timing of the Head Tax itself was no coincidence: it was implemented the same year that the CPR was completed. Officials no longer needed the underpaid labour that had been so crucial to their success, and hoped, instead, to discourage any further immigration from China. The Head Tax was also designed to make it prohibitively expensive for those already in Canada to bring over their wives and families.

Extreme as this is to our modern eyes, this policy was widely popular at the time, reflecting pervasive anti-Asian sentiments common among European Canadians of the day. Even Wilfrid Laurier — who became Prime Minister in 1896 and is often lauded for his promotion of immigration — was not immune. In a 1903 speech, he voiced his scepticism of immigration from China, concluding pessimistically that “it is very doubtful whether assimilation of the two races could ever take place”.

Others took their xenophobia much further. On September 7th, 1907, Vancouver’s mayor and other leading European Canadian citizens organised a rally of the “Asiatic Exclusion League”. This gathering of several thousand quickly degenerated into a violent mob that attacked and vandalised Chinese and Japanese Canadian homes and businesses for two days straight. By the time order was finally restored, tens of thousands of dollars in damage had been done, and our local Asian communities had been harshly reminded of the precariousness of their place in Canadian society.

With the Canadian economy struggling, anti-Asian sentiments had grown so strong by 1923 that the new Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King felt compelled to introduce the Exclusion Act, which came into force on Dominion Day, July 1st, a day we now — ironically — happily celebrate Canada’s multicultural present.

Under the terms of the Exclusion Act, immigration from China was all but ended: only diplomats, some merchants, university students and Canadian-born students already studying overseas were exempted. And those already in Canada now faced additional restrictions: all people of Chinese descent, whether Canadian born or naturalised, were required to register and carry photo identification. These racist restrictions would remain in force until 1947. Their impact was profound: over this twenty-five year period, less than a hundred Chinese immigrants were allowed to legally enter Canada.

The consequences for those already living in Canada were especially traumatic. Separated from their families, some never saw their wives or children again. Many older men ultimately felt compelled to retire back to China. An extreme gender imbalance also occurred, according to Dr. Henry Yu, a UBC professor and grandson of an immigrant who was himself forced to pay the Head Tax. The Exclusion Act, Yu notes, “basically made it impossible for many of them… to marry someone and have kids turn into grandkids. Many of them would die alone literally, growing old alone except for these other men in these cafes." Not surprisingly, many local communities began to shrink.

These events were truly tragic, and are indicative of our complicated and often troubling past. But they are not the full story. In fact, we should also remember 1923 for another, far more uplifting reason: it was the year that the concerted effort of our local Chinese Canadian community forced the school board to abandon its plan to permanently segregate Victoria’s public schools.

In the fall of 1922, as the Exclusion Act was being drafted in faraway Ottawa, the Victoria School Board, under the leadership of longtime chair George Jay, was busy commissioning a dilapidated building and hiring staff for a school where students of Chinese-descent would be taught separately from their European-Canadian peers. But then, suddenly, on September 15, all of the Chinese Canadian students disappeared as their principal walked them towards their new school. The message from the community was soon heard loud and clear: the students would not be returning until the segregation policy was abandoned. This school strike dragged on for an entire year until Jay and the board were forced to concede, facing widespread criticism for all the resources they had expended on their failed initiative.

This was by no means the first time that Victoria’s Chinese Canadian community had stood up and rallied for their rights. Years earlier, in 1907, they had successfully sued to overturn a discriminatory school entrance exam policy that was being applied only to their children.

Considered together, the passing of the Exclusion Act and the successful school strike make the hundred-year anniversary of the 1922-23 school year a centennial truly worth commemorating. These events remind us how complex our shared history truly is. As British Columbians and Canadians, we are the inheritors of a complicated legacy, a story defined both by regrettable oppression and remarkable agency and resilience.

The good news is that we have come so far in the last hundred years.

Consider the reality that, today, Canada welcomes more immigrants from China than any other country on earth, followed closely by the Philippines and India. Then there’s the fact that British Columbia was the first jurisdiction in Canada to have both a South Asian Canadian premier, Ujjal Dosanjh, and a Chinese Canadian Lieutenant-Governor, David Lam.

Canada also began the new millennium with a Chinese Canadian Governor-General, Adrienne Clarkson, who had first come to Canada as a refugee during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. Her story is all the more remarkable because she was one of the few able to circumvent the Exclusion Act, on account of her father’s political and entrepreneurial connections.

Another important milestone was reached only last year: in October 2022, Ken Sim became the first Chinese Canadian elected as mayor of Vancouver, a city once led by politicians who literally incited the ransacking of their own Asian communities.

Fittingly, 2023 will also be the year that nearby George Jay Elementary School will be renamed to reflect the reality that it is now home to perhaps Victoria’s most diverse, multicultural student population.

The fact that we have come so far, overcome such a dark past, and become such a multicultural society speaks volumes about the efforts, contributions and resilience of our Asian Canadian communities. It also reinforces our collective responsibility to continue to do the work, to combat the lingering threat of anti-Asian hate that resurfaced so jarringly during the recent pandemic.

We owe it to our Asian Canadian neighbours — and indeed ourselves — to do better, to be better. To celebrate their heritage as our own. Because Asian Canadian history IS Canadian history. And we are all in this together.

If you would like to learn more about the rich history of BC’s Chinese Canadian community — or Asian Heritage Month more generally — please visit one of our campus libraries. In the Middle School, you will find a book display, a heritage walk and a recommended reading list here. The Senior School library reading list can be found here, and features a visual timeline of milestones in Chinese Canadian history. For those looking for a great way to spend an afternoon, why not visit Victoria’s Chinatown Museum in historic Fan Tan Alley?