This year, as part of the Middle School's unfolding STEAM initiative, Grade 7 and Grade 8 students have the opportunity to further develop their design thinking mindset from Grade 6 ADST (Applied Design, Skills, and Technologies) and sink their teeth into one of three streams—Computer Science, Communication and Media Design, and Engineering and Design.

In our Engineering classes this term, we have been embracing the struggle of real-world problem-solving with a bridge-building challenge. The task is straightforward enough: construct a model bridge from basic materials that will cross a 75-cm gap and support as much weight as possible.

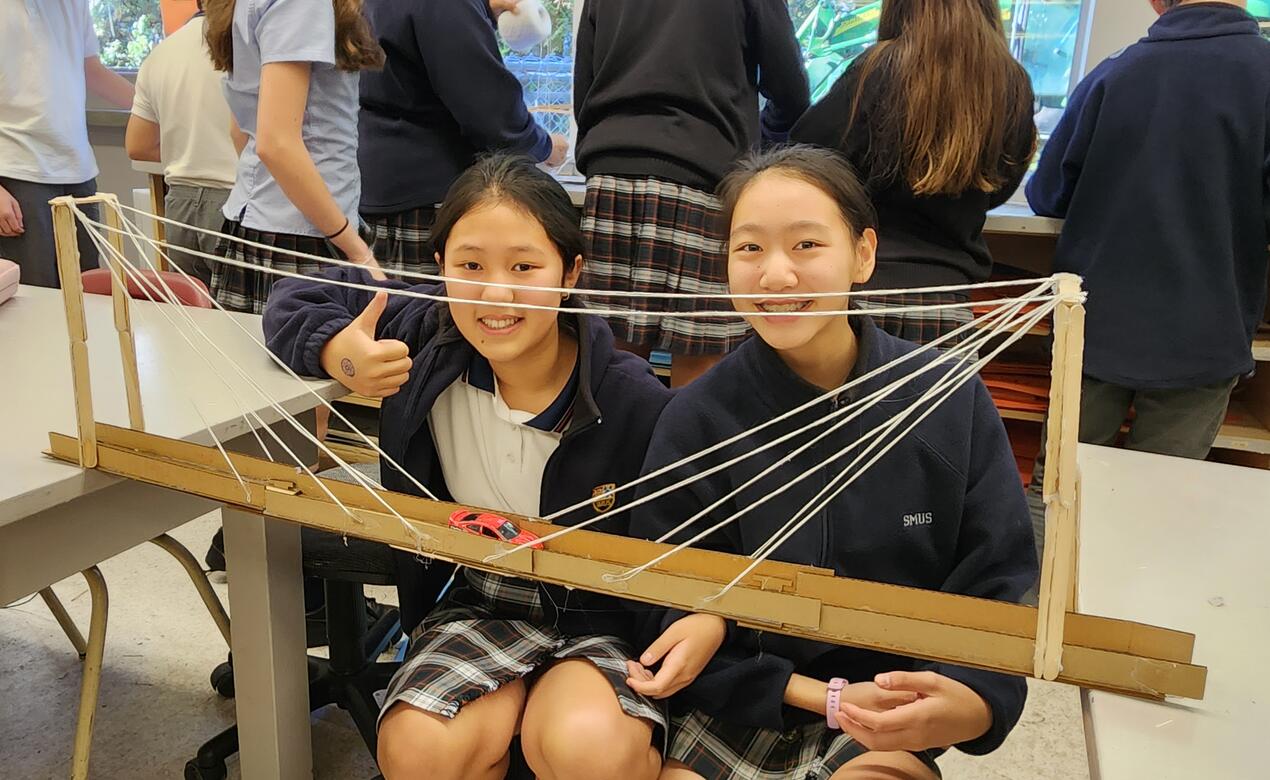

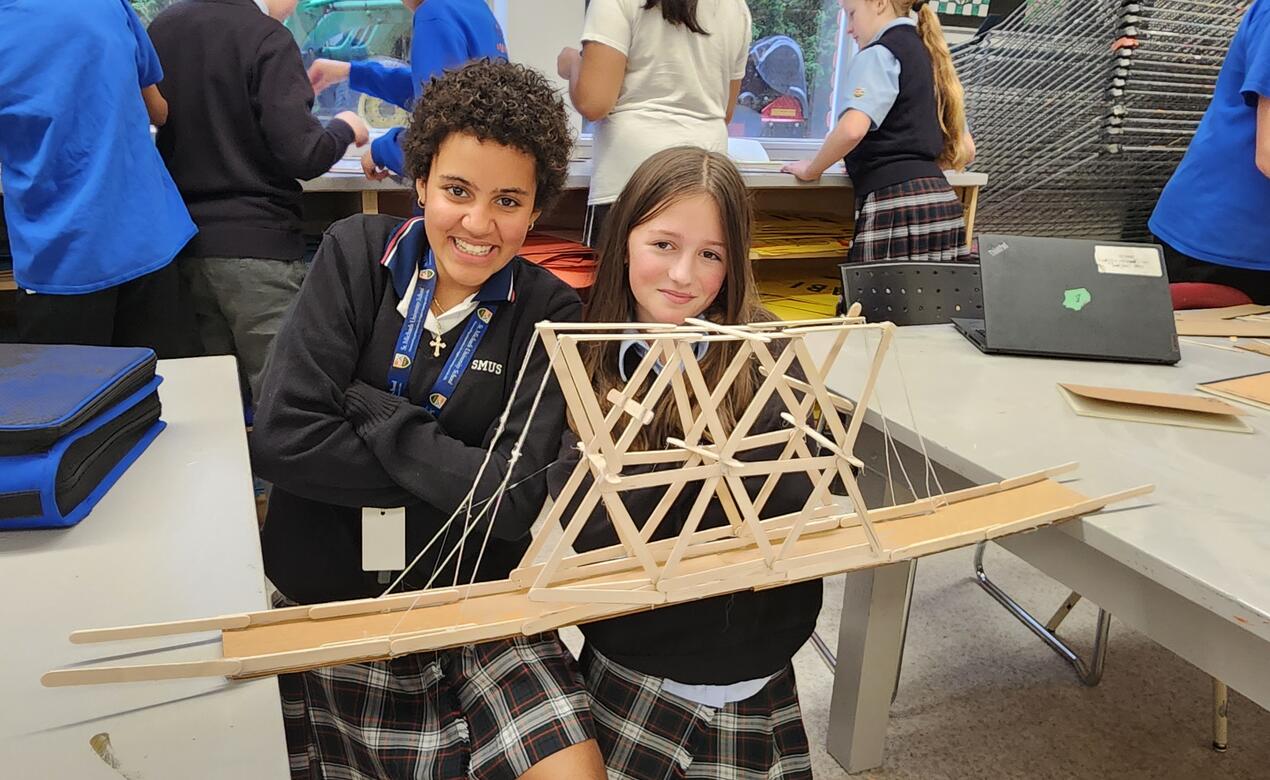

With very few other limitations or parameters, this assignment quickly became an opportunity for some students to test out inventive new approaches, while others chose to replicate existing real-world designs. After researching the options, one team decided to recreate a da Vinci bridge (an interlocking design that requires no connectors and, ingeniously, tightens the structure even further with an increased load). Another team opted for an elegant cable-stayed design, reminiscent of the iconic X-towered bridge in São Paulo.

A third team chose to laser-cut their ration of cardboard into identical vertical slats, then glued them together with popsicle stick reinforcements to form a rigid plank to end up with what we will generously call a “minimalist design”, which—infuriatingly—trounced all the others in terms of load-bearing strength.

The heated follow-up debate on whether a bridge has truly “failed” if it’s bent at a 90-degree angle, but still holding up several textbooks, also raised an important point: shouldn’t we hold our models to the same standards as bridges in the real world? If the Johnson Street Bridge started curling inward one day, would we still be proudly announcing that it “hasn’t collapsed yet”?

With this hands-on approach to learning came its fair share of planning and reflection. Students put their drafting skills to the test with concept sketches, technical diagrams, and orthographic projections of their bridges in their design journals. They then reflected on their work with the three basic questions we ask ourselves after each attempt: What worked? What didn’t? And how do we make it better?

And of course, we teachers wouldn’t be good role models if we didn’t also follow this reflection process with our lessons. After adapting the original task of having an entirely laser-cut cardboard bridge, I’m kicking myself for not limiting the amount of additional resources they were allowed to use (it’s become very clear that there is a direct correlation between the quantity of glue and task success variables). I also wish we had begun by researching the fundamentals of bridge structures and the advantages and disadvantages of each design.

These will be important notes for next year. But, if students are having fun, engaged, and learning, I think we can still chalk it up as a win.